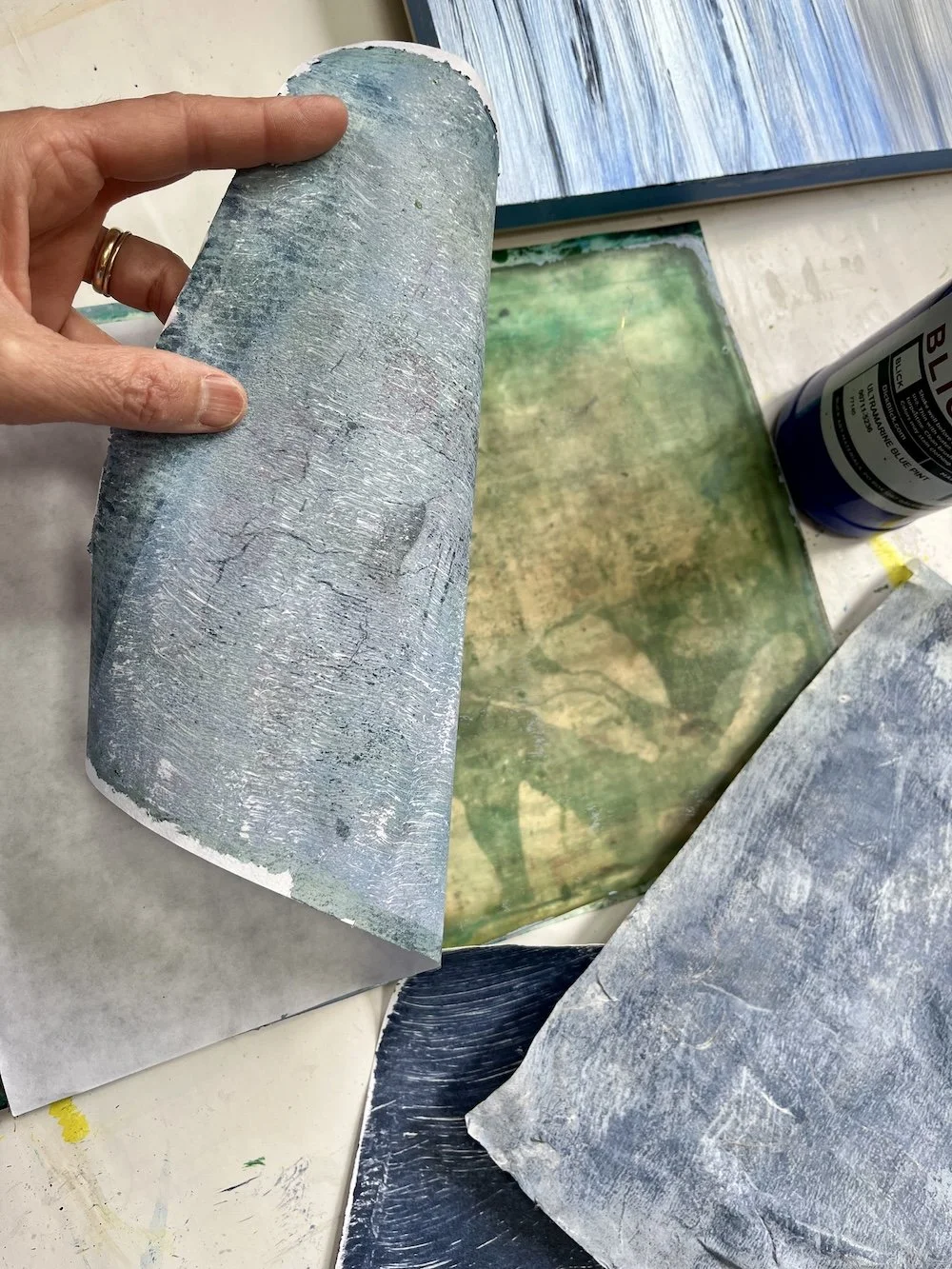

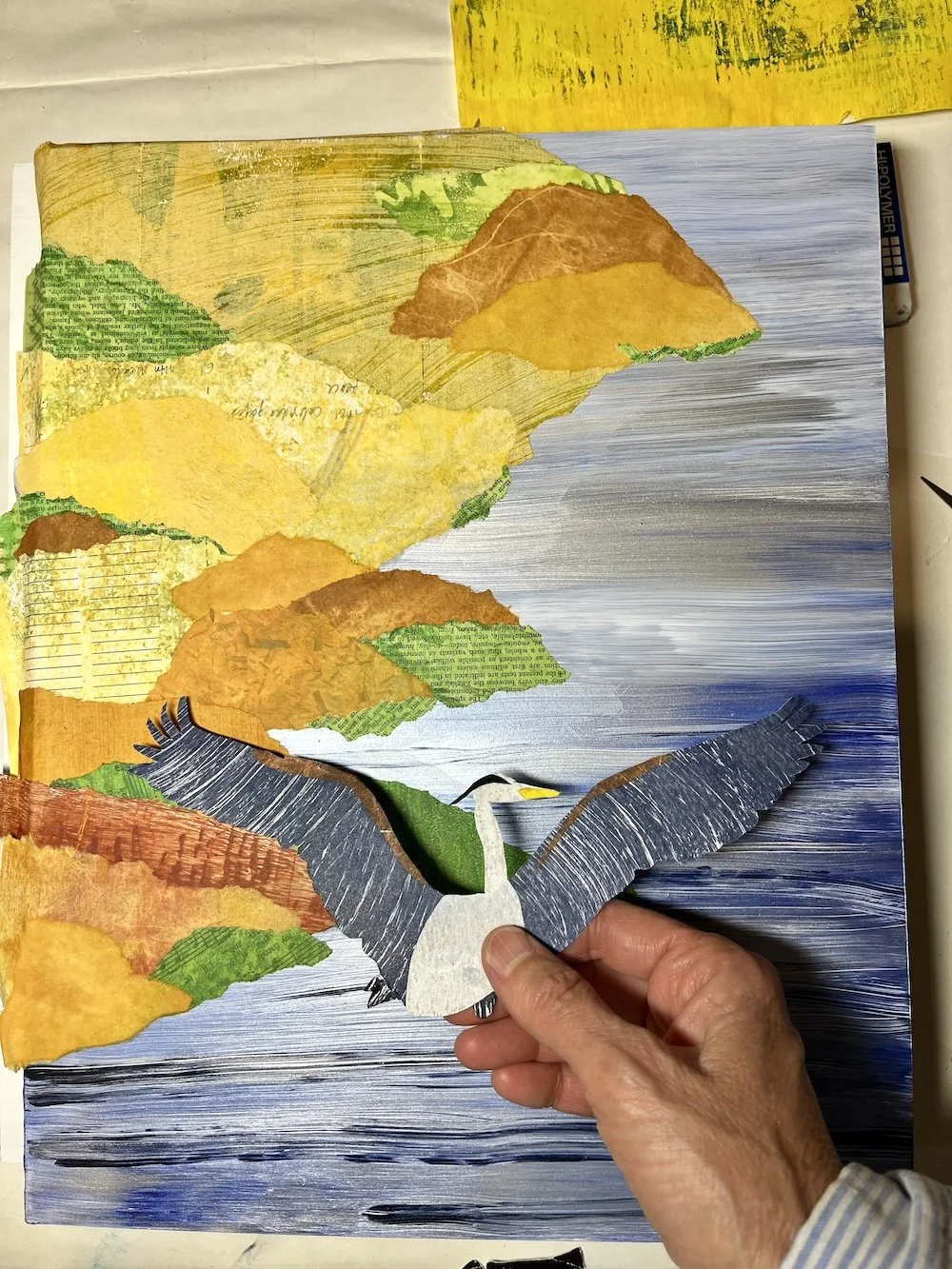

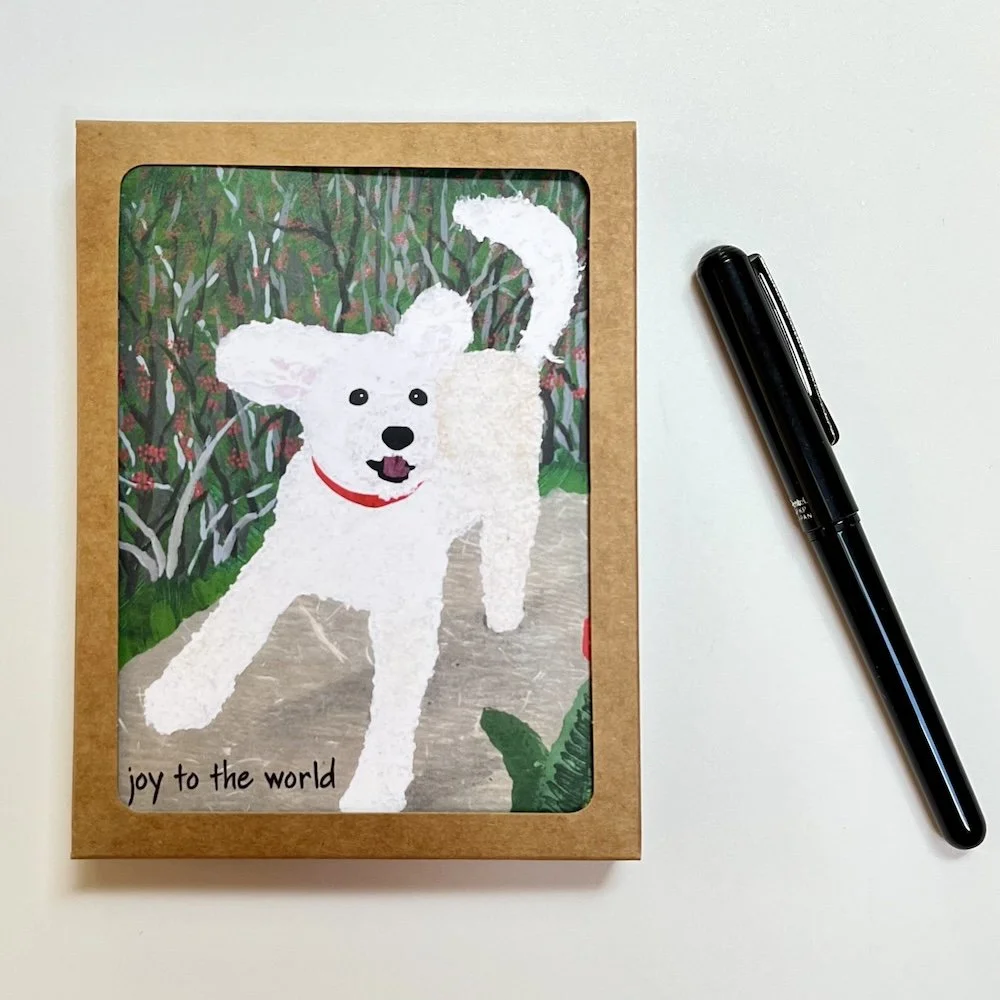

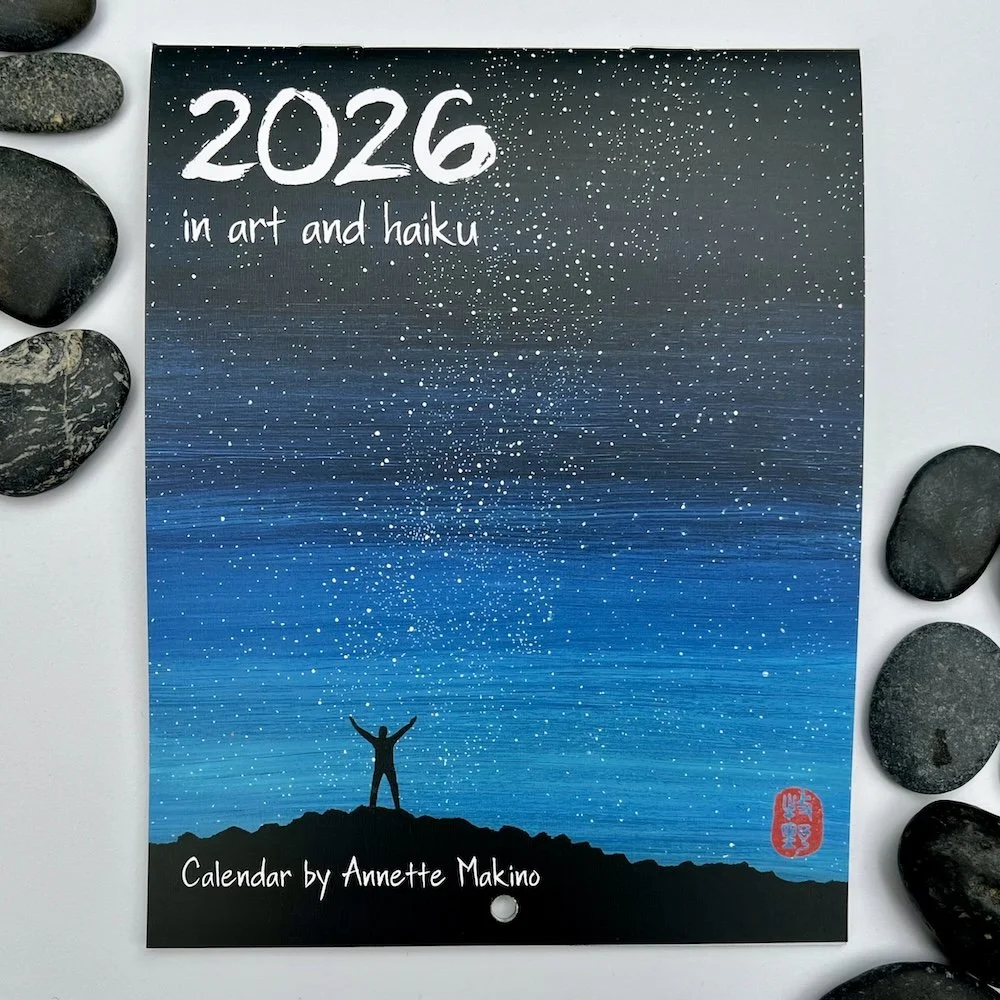

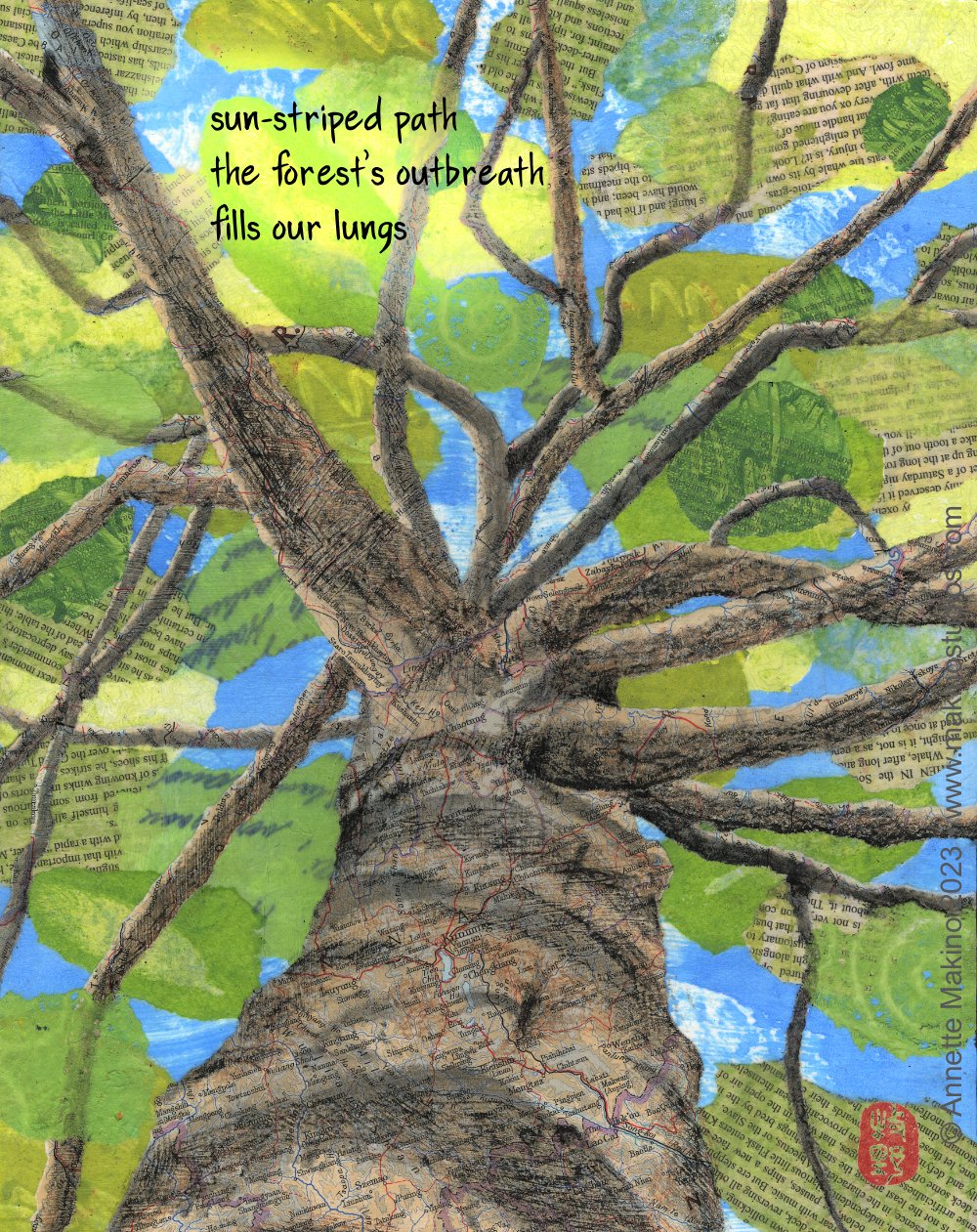

“touch of frost” is an 11x14 mixed media collage made with paper and paint on cradled wood. This is part of my 2026 calendar. A version of boxed holiday notecards reads “joy to the world.” © Annette Makino 2025

I must admit, these short, dark days are hard to take. Being more of a night owl, I miss part of the limited daylight we get in the mornings, then feel shocked and cheated when twilight approaches before 5 p.m. So unfair!

How to cope? I try to appreciate merino wool sweaters, flannel sheets, and our wood-burning stove. And ignore the fact that spring is still months away—in fact, it’s not even officially winter yet! Still, it’s cold, dark and damp, and I struggle.

otter dusk

what’s left of the light

slips downstream

But it turns out that the worst is already behind us: yesterday saw the earliest sunset of the year here, at 4:48 p.m. From today on, the days will feel longer even though the winter solstice is not until December 21. So hurray for the return of the light!

I’m finding that the best way to make my way through this hard-to-love season is to look for glimmers of joy. Last Thursday my husband, son and I went tide pooling during a ridiculously beautiful sunset (see below), which we would have missed had the sun set after dinner.

Sunset at Houda Point in Trinidad, CA, during a minus tide. December 2025. Photo: Annette Makino

a cormorant air-dries its wings

sea-washed stones

Saturday night we took part in Arts Alive, a monthly cornucopia of local art and music during which Paul and I got to join our old choir for a few songs. Sunday we watched a fun play featuring an evil sock puppet orc who sings a hilarious but poignant solo. On Monday morning I taught a haiku workshop to a class of surprisingly engaged high school sophomores who impressed me with their creativity.

Holiday season brings the special pleasures of gathering with family, friends and community. This coming weekend, I’m looking forward to having a Makino Studios booth at the Arcata Holiday Craft Fair. As my only in-person event this season, this is a rare chance to meet face-to-face with my customers and to hear their stories. That is a key part of what keeps me going in my art biz.

However winter hits you, here’s wishing you bright glimmers to celebrate in this dark season. Happy holidays!

touch of frost

the dog smiling

from nose to tail

warmly, Annette Makino

•

Happy merry holidays!

Makino Studios News

Free shipping: Use promo code HOLIDAY2025 at checkout for free shipping on all Makino Studios orders, no minimum. Good for first-class shipping within the U.S. One promo code per order. Promotion ends at midnight this Sunday, Dec. 14, 2025.

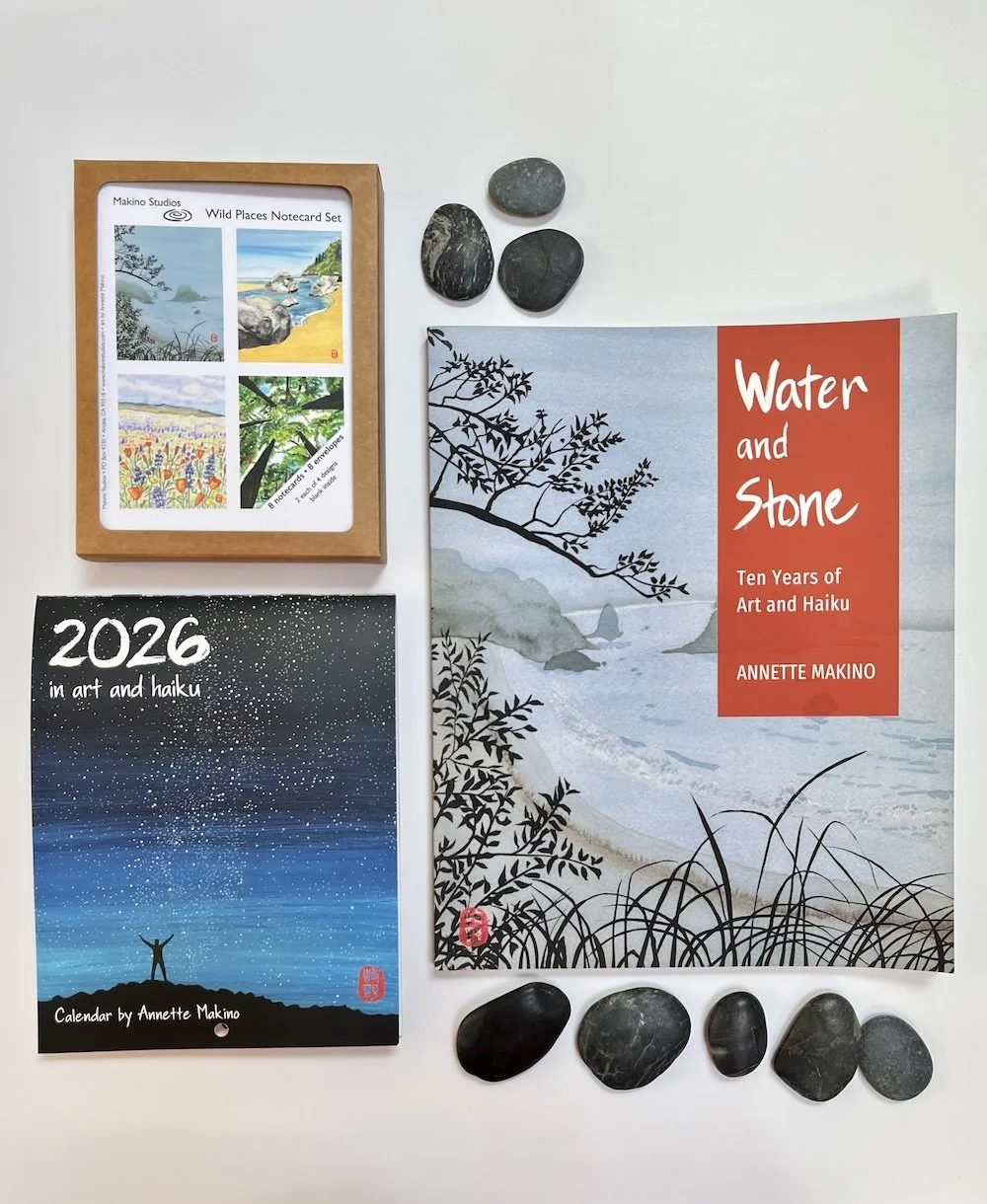

2026 mini-calendars: Small calendars of art and haiku make great holiday gifts! They feature 12 colorful Asian-inspired collages with my original haiku. $12 each.

Cards: Holiday, birthday, sympathy or everyday . . . right now there are around 80 Makino Studios card designs to choose from. I also have notecard sets, including holiday designs.

Water and Stone: My award-winning book of art and haiku includes 50 watercolor paintings with my original poems. Cost is $25. I will sign them on request—just send me an email after you order.

Holiday shipping: The US Postal Service advises that to ensure that packages arrive by Dec. 25, they should be shipped by Dec. 17.

Arcata Holiday Craft Market: Featuring food, music, and local vendors, this festive fair takes place 10 to 5 on Saturday, Dec. 13 and 10 to 4 on Sunday, Dec. 14 at the Arcata Community Center in Arcata, CA. Look for the Makino Studios booth on the lefthand side of the main room. This will be my only in-person event this season. Admission is a $2 donation benefiting the Youth Development Scholarship Fund.

Made in Humboldt fair: The “Made in Humboldt” event at Pierson Garden Shop in Eureka, CA runs through Dec. 24. There are more some 300 local vendors; Makino Studios items include my 2026 calendars, books, prints and boxed notecards.

CREDITS: “otter dusk” - Acorn, Fall 2025; “a cormorant” - Nowhere Else: Haiku North America 2025 Anthology, Eds. Michael Dylan Welch and Chuck Brickley, Press Here, 2025; “touch of frost” - 2026 in Art and Haiku, Annette Makino, 2025